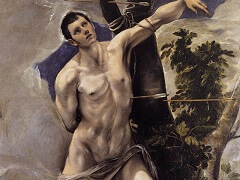

Christ Carrying the Cross, 1594-1604 by El Greco

What, from the first, distinguishes the Puritanism of the southern Counter Reformation from that of the northern Protestant Reformation, is that the Catholic temple-purifying, temple-strengthening authoritarian rigidity was partly submerged or concealed by the tremendously popular and fluid stratum of pious emotionalism. Ignatius Loyola's Exercises reflect this most successfully. The anxiety-stricken and at the same time sophisticated Catholic humanity found a temporary respite, a psychological vacation, in the very exaggeration and primitiveness of this sentimentality.

Thus, El Greco's image of Christ bearing the Cross, extravagant as it might be for modern taste in its honeyed, comfortably pious, and dramatized sentimentality, must have had a totally different effect on those of El Greco's contemporaries in Toledo then so influenced by Levitical and Jesuit thought for whom this icon was made.

El Greco's Christ is perfection complete: the image of perfect humanity. Nothing can be said against this image thus nothing about it. It does not touch anything and nothing can touch it. It can only be shown or revealed by itself.

Perfect and dramatic arc the eyes of El Greco's Christ and the precious, overemphasized tears in them. Perfect and dramatic, the virility of his head, his neck, and his robust shoulders. And perfect also and dramatic the feminine beauty of his hands. The tapering fingers of the right hand are without any blemish of any activity on them. The affected bend of the left hand's little finger is simply a gratuitous condescension of its grace. The hands that are going to be disfigured on the Cross do not touch the Cross, do not touch anything. They should not be touched either. They are shown to us they reveal themselves to us in their passive beauty.

A golden, crepuscular warmth of Venetian colors and light adds more sentimental sweetness to the Savior's figure.