El Greco was a foreigner all his life long. He was a foreigner in his own birth land, Crete: the luminous island, the proud torchbearer of fallen Byzanrium, and since the seizure of 1204, humiliated, foreign to itself, the helpless subject of Venice. Foreigner he was when, young icon painter-artisan, he went (a little after 1560), like so many of his compatriots, to the still busy, still daring city of Venice, to live there, to work, to watch, and to absorb the great West at large. Foreigner he was in Rome, whither from the Venetian lagoons his adventurous will or some other urge more material directed him - from 1570 to 1576? or from 1570 to 1572 and then back to Venice again ? - before his final exodus to Spain. And foreigner he remained in Spain, foreigner in Toledo, where he settled about the year 1577, and where he died April 4th, 1614. He was called El Griego - the Greek-by his Toledan co-citizens; in all the official documents, Dominico Theotocopuli (or Theoocopulo), Griego. Revealingly, he signed his pictures in Greek: Domenicos Theotocopoulos. And it was by Italian form of his name, Dominico Greco (not even the Castilian form, Griego), that he is referred to in El Arte de la Pintura, by the painter scholar Francisco Pacheco, the Sevillian, who visited El Greco in 1611 and surely used the name by which the aged artist must have been known professionally.

Foreigner he was until the end, even beyond the end: a scarcely noticed foreigner-ghost, visitor-ghost of the following centuries; his very name, unknown in Crete , was also soon forgotten, if ever really retained, in Italy (the last trace of Greco's passage in Italy is the reference to him by Mancini, Pope Urban VIII's physician, about 1614) . A puzzling foreigner-ghost he was to the nineteenth-century Romanticists, who were attracted by the aura of eccentricity: this legend of eccentricity, of madness even, having originated in the whispered slanders of Toledan sacristies of his time, and culminating in the twentieth-century "scientific" theories - now fully refuted-of El Greco's insanity, his astigmatism and other aberrations.

Not until our own age, conscience-torn and foreign to itself, was full and exalted citizenship given to him: in critical literature notably by Manuel Cossio's classical and unsurpassed work, El Greco, published in 1908; and more vitally, because couched in terms of Greco's own pictorial idiom, by Paul Cezanne.

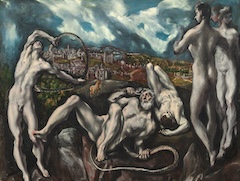

During the crucial period Pablo Picasso was working on that keystone of modern painting, the Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907), he visited his friend Ignacio Zuloaga in his studio in Paris and studied El Greco's opening of the Fifth Seal, which left an indelible impression. For Picasso, too, El Greco was both the quintessential Spaniard and a precursor of Cezanne and Cubism. Franz Marc, Paul Klee and the members of the Blue Rider group admired El Greco as a painter who 'felt the mystical inner construction' of life: someone whose art stood as a rejection of the materialist culture of bourgeois society. Expressionism was also inspired by El Greco's expressive distortions and Jackson Pollock, a key player in the abstract Expressionism, produced sixty drawing compositions after El Greco.

The twentieth-century view of El Greco is encapsulated in widely read essay published in 1950 by Aldous Huxley:

In looking at any of the great compositions of El Greco's maturity we must always remember that the intention of the artist was neither to imitate nature nor to tell a story with dramatic verisimilitude. Like the Post-Impressionists three centuries later, El Greco used natural objects as the raw material out of which, by a process of calculated objects as the raw material out of which, by a process of calculated distortion, he might create his own world of pictorial forms in pictorial space under pictorial illumination. Within this private universe he situated his religious subject matter, using it as a vehicle for expressing what he wanted to say about life.”

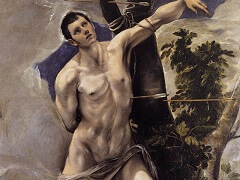

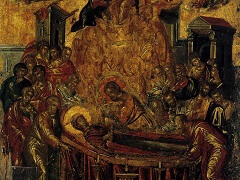

The last several decades have brought a number of refinements to our knowledge of the artist. For one thing, we can now identify a small group of icons he painted in his native Crete, prior to his move to Venice in 1567. These works remind us of the Neoplatonic, non-naturalistic basis of El Greco's art, before he set about transforming himself into a disciple of Titian and an avid student of Tintoretto, Veronese and Jacopo Bassano. We also possess El Greco's copies, with the artist's annotations in the margins, of the architectural treatise by Vitruvius and of Vasari's lives. The opinions he voices must be read against the works, but also understood in the context of late sixteenth-century debates about the nature and function of art.

El Greco was in Rome from 1570 to 1576, but the contacts he established with other artists remain nebulous: our firmest guide to his response to what he saw are the paintings, of which an exemplary group is included in the exhibition. What can be said is that, despite a letter of introduction to the powerful Farnese family, his paintings seem to have met with no more success in Rome than they had in Venice. He received no major commissions, and his work was confined to modestly scaled devotional paintings and portraits. El Greco reputedly criticized Michelangelo's abilities as a painter - an opinion that would have generated little confidence in his abilities and offended the Roman art establishment (Michelangelo had died in 1564, but his prestige in Rome was undiminished).

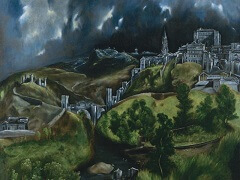

These were not auspicious beginnings for his career in Spain, where he moved in 1576. In Madrid, his bid for royal patronage from Philip II failed. (For his austere retreat at El Escorial, Philip wanted clearly decipherable pictures that advertised his orthodoxy, not paintings that celebrated artistic genius.) Only in Toledo, where he received two major commissions, did El Greco meet with the success an artist of his caliber might have expected. It was in this ancient city, which El Greco immortalized in one of the most celebrated landscapes in Western art, that he found, at last, a sympathetic circle of intellectual friends and patrons and forged a highly profitable career. In Toledo he became the artist we have come to admire, and we need hardly be surprised to learn from his contemporary, Francisco de Pisa - whose portrait he may have painted - that, then as now no visitor to the city failed to go to the church of Santo Tome to admire The Burial of the Count of Orgaz.

Toledo may have been far removed from the artistic ferment of Rome, but it was no bastion against the forces - cultural as well as artistic - that were to shape the art of the seventeenth century. It is all too easy to treat El Greco's achievement in isolation, as though it were an aft outside its time - an art waiting to be discovered by the modern era. It comes as something of a shock to realize that, when El Greco died in 1614, Caravaggio and Annibale Carracci - the creators of the new Baroque style - had been buried for four and five years, respectively. Ribera was already active in Rome, and one of Caravaggio's most individual followers, Juan Bautista Maino, was busy in Toledo itself (as had been the great still-life painter Juan Sinchez Cotin). In 1611 Diego Velazquez, the presiding genius of seventeenth-century Spain, was apprenticed to Francisco Pacheco in Seville. It is enough to mention these figures to realize that in important respects El Greco's art belonged to the past, not the future - to the world of Mannerism, with its emphasis on the artist's imagination rather than the imitation of nature.

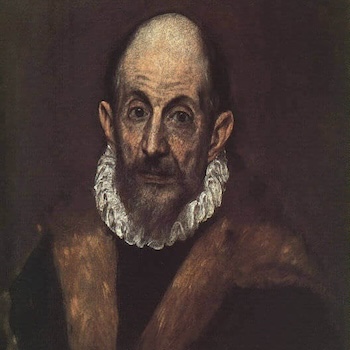

Pacheco, whose curriculum of study formed the young Velazquez, visited El Greco in his studio in Toledo in 1611 and recorded seeing the plaster, wax and clay figures from which El Greco worked. He did not approve of this method, which El Greco had doubtless learned from Tintoretto in Venice: Pacheco advocated a real human figure rather than something modeled in clay. It is thus not surprising that El Greco's pupil Luis Tristan abandoned his master's esoteric Mannerist style for Caravaggesque naturalism. And yet, although he disapproved of the extreme distortions of El Greco's late religious paintings, Pacheco could not deny El Greco's place among the great painters, 'for we see some works by his hand so plastic and so alive (in his characteristic style) that they equal the art of the very best'. He may have had in mind El Greco's portraits, which Velazquez also prized so highly.

Paradoxically, it is precisely the most extravagant flights of El Greco's fertile imagination - works in which the figures are elongated beyond credibility and their forms dematerialized by a flickering brushwork - that are most prized today (they form the core of this exhibition). In the present age of secularism, this is nothing short of miraculous. However, in his indispensable study of the profound changes of taste, fashion and collecting in nineteenth-century France and England - Rediscoveries in Art - Francis Haskell reminded us:

The real "discoveries" that occurred between about 1790 and 1870 were not so much of Orcagna or Rembrandt, Vermeer or El Greco, Sandro Botticelli, Piero della Francesca or Louis Le Nain, as of a multitude of contrasting qualities each apparently divorced from those associations (of religion or of a certain concept of art itself) that were once thought to be indissolubly lined to them."

No other great Western artist moved mentally - as El Greco did - from the flat symbolic world of Byzantine icons to the world-embracing, humanistic vision of Renaissance painting, and then on to a predominantly conceptual kind of art. Those worlds had one thing in common: a respect for Neo-Platonic theory about art embodying a higher realm of the spirit. El Greco's modernism is based on his repudiation of the world of mere appearances in favor of the realm of the intellect and the spirit.