The Opening of the Fifth Seal, 1608-14 by El Greco

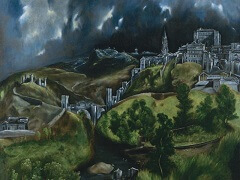

The Opening of the Fifth Seal is a large fragment of one of three altarpieces El Greco contracted to paint in 1608 for the church of the Hospital of Saint John the Baptist (the Tavera Hospital). Located just outside the walls of Toledo, the hospital was founded in 1541 by Cardinal Juan Tavera (1472-1545), who is buried in the church. The administrator responsible for the commission was Pedro Salazar de Mendoza (c. 1550-1629), an admirer of El Greco with strong views about the function of works of art. He is known to have owned no fewer than six paintings by the artist, probably including the View and Plan of Toledo (fig. 9, p. 27), which gives prominence to the hospital (shown floating on a cloud). Thirteen years earlier, in 1595, El Greco had designed for the main altar a wooden tabernacle, or custodia, adorned with four small statues of the Fathers of the Church and another of the risen Christ. The tabernacle survives, though in a sadly dilapidated state, and the statuette of the risen Christ (fig. 49, p. 174) - of exceptional beauty and great importance, as it provides an idea of the appearance of the sculptural models in plaster, clay and wax that El Greco worked from - is normally displayed in the library.

Of the 1608 project for the altarpieces, three pictures survive: an Annunciation (Coleccion Santander Central Hispano, Madrid; the picture has been cut: the upper portion, showing a choir of angels, is in the National Gallery, Athens); a Baptism (installed on a side altar in the church); and the picture in the Metropolitan Museum known today as The Opening of the Fifth Seal but perhaps best described as Saint John the Evangelist witnessing the Mysteries of the Apocalypse - the way a small replica or model for the picture was described in the 1614 inventory of El Greco's studio.

This was El Greco's last large-scale undertaking, and he did not live to complete it: in the 1614 inventory we find its components described as 'the paintings destined for the hospital, begun', followed by 'the wood frames, not sculpted, for the lateral altarpieces', and 'the altarpiece of the high altar without its columns, tympana and sculptures'. Also listed are two canvases for the tympana (or pediments) of the lateral altarpieces. El Greco's son Jorge Manuel continued to work on the altarpieces and by 1621 the frames of the lateral ones had been prepared for gilding and that for the high altarpiece had been finished. Jorge had completed The Baptism, which was for the high altar, but not the paintings for the lateral altars, which remained only sketched in ('bosqueados'). Eventually, Jorge Manuel brought The Annunciation to completion, thereby spoiling with his pedestrian imagination and merely competent brush what his father had begun, just as he had spoiled the principal figures of The Baptism. Fortunately, The Opening of the Fifth Seal remained as El Greco had left it. Although cut down in 1880, when it was re-lined by a restorer of the Prado (as much as 175 cm may be missing from the top and as much 20 cm from the left side), and badly damaged, the Metropolitan's canvas remains the best testimony we have of the visionary heights of El Greco's late style.

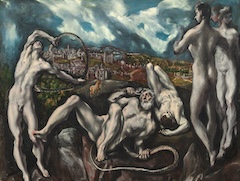

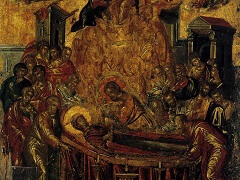

In the foreground is the incredibly elongated, ecstatic figure of Saint John, his head turned imploringly heavenward, his arms raised. Behind him are two groups of figures. The three on the right, seen against a green drapery, are male and reach upwards for white garments distributed by a flying cherub. The four on the left are shown in front of a mustard-colored cloth. Two are male, two female, and they seem to be covering (or uncovering) themselves with the yellow drapery. It was Cossio who, in 1908, first proposed that these features suggested a visualization of the Book of Revelation, when Saint John the Evangelist witnesses the breaking of the Fifth Seal by the Lamb of God:'... I saw under the altar the souls of them who were slain for the word of God, and for the testimony which they held: And they cried with a loud voice, saying, "How long, O Lord, holy and true, does thou not judge and avenge our blood on them that dwell on the earth?" And white robes were given to every one of them; and it was said unto them, that they should rest yet for a little season, until their fellow servants also and their brethren, that should be killed as they were, should be fulfilled.' Unlike Durer, who illustrated this passage in the upper register of one of his celebrated woodcuts of the Apocalypse, and Matthias Gerung, whose 1546 woodcut offers interesting analogies with El Greco's painting (it includes the figure of Saint John in the foreground), El Greco shows no altar. However, it is possible that an altar may have been represented above, as in Durer's prints. The towering figure of Saint John in the foreground shifts the emphasis from an illustration of an incident to Saint John and his vision.